Are we archaeologists, or are we not?

Introduction

This article presents some personal thoughts related to the concept of being an archaeologist. Although my article will touch upon issues such us real and/or fictional perceptions of archaeology, as well as the process of ‘becoming’ and the state of ‘being’ an archaeologist, I plan not to monopolise the discussion with philosophical terminology. Also, I plan not to theorise over such concepts in sheer disappointment of those expecting a theoretical paper. In fact, the discussion is going to be humorous, not only because I enjoy conducting it in such manner, but also because many of the concepts and situations explained further below could easily classify as surreal. The aim of this article is to make other archaeologists think a bit more about our job, our own existence and our contribution as a professional body to human progress and evolution; the immediate result, however, will probably be to expand my circle of archaeologists who hate me. Personally, I am fine with both.

Questions and structure of the article

The article's title says it all from the very beginning: are we archaeologists, or are we not? In other words, who is regarded an archaeologist today and who is not? Furthermore, what does it take to become an archaeologist and what should not be happening? In order to unravel my thoughts, I plan to divide this article in three sections.

In the first section, I will discuss modern popular perceptions of archaeology and contrast them with the academic perspective. I will talk about the ‘Great Divide’ between academia and commercial archaeology, which may in theory be invisible, in reality, however, each one of us can see it everywhere inside the discipline. In the second section, I will focus on the process of becoming an archaeologist, which is commonly believed to be through academic studies. I plan to discuss the different types of archaeological training that are offered today, and also focus on some of the options that are available after graduation. In the third section, I will talk about the state of being an archaeologist, which is the most difficult part of all. In general, being an archaeologist requires that someone has a job within the discipline. This does not necessarily mean that someone who has only studied archaeology has no right to be called an archaeologist; this is definitely not true; however, for the purpose of this article, the state of being an archaeologist is associated with practising archaeology at a professional level and earning a living out of it. Practising archaeology involves a variety of tasks and decisions, which are adopted and adapted according to the complexity of each project. Here, my intention is not to discuss such complexities in detail, but to bring up some practical issues that archaeologists need to consider when seeking for jobs.

What I need to make clear for the beginning, just in case somebody is bored of reading ‘yet another article’, is that my entire approach will be based on my personal experiences from British and Greek archaeology. Whatever is to be discussed in the following paragraphs is the result of personal involvement, personal thought and personal understanding of matters, and I need to apologise from the beginning to any of my colleagues who might feel uncomfortable with what is to be said. To quiet things down, however, I must stress that I never planned on writing an article to attack and undermine our discipline. If there is indeed anything that can be undermined in archaeology, then we all need to sit down and do something about it. This article is only meant to motivate some colleagues to revisit the functionality of our discipline, and most preferably soon.

Popular perceptions of archaeology: fiction, misuse and reality

As an undergraduate student at the Greek Open University, I studied an introductory volume on archaeology, which included a whole chapter on popular perceptions of archaeology today. This chapter focused on how such perceptions circulate through the media and what their effects on the broader public. Furthermore, the chapter included a section on pseudo-archaeology, which discussed the deliberate misuse of archaeology for generating false perceptions of the past, in order to manipulate the public for various social, political and economic reasons. Most of this volume was written by my first mentor in archaeology and I still consider it one of the most important texts I have ever read. At that time, it appeared to me as revelation in the darkness of my understanding.

Although I had some voluntary experience from archaeological excavations prior to my studies at university, in reality, I had absolutely no clue what I was doing during such digs other than following instructions and trying not to ridicule myself. It was definitely obvious to everybody that my theoretical understanding in archaeology was completely absent. Even worse, during the earliest years of my life and long before studying at university, I had been exposed to pseudo-archaeology and I had poisoned my intentions to knowledge. Now I feel completely embarrassed admitting it, but back then, I flirted with the idea that many of the greatest civilisations of the past, such as the Hittites, the Sumerians and the Egyptians, had been in contact with alien lifeforms, from whom they received advanced scientific knowledge. I was also fascinated by the possibility that the Atlantis might had been a factual alter ego of our current civilisation, and that the Odyssey might had taken place in the Atlantic Ocean. At least, I was smart enough to know that real archaeology had nothing to do with Indiana Jones, although I always admired the man: not only had I watched all Indiana Jones films and Young Indiana Jones chronicles (more than twice), but as a high-school student back in the 1980s, I had played every Indiana Jones computer game on these primitive machines that we used to call ‘computers’.

Reading that introductory volume on archaeology at university only confirmed to me how stupid I had been in the past, at least before deciding to educate myself properly. All of a sudden, I realised that ancient humans were highly intelligent, inventive and full of imagination; therefore, ancient cultures, which were the products of such intellect, were not to be undermined in favour of any external intervention. Although the rationale and the approach of ancient humans to technology was different compared to ours, their ingenuity and planning was similar; therefore, I realised that by undermining their actions we only undermine our own species. Of course, there are many things that our species has been doing wrong for ages, particularly in relation to power and control over natural resources; however, archaeology is one of these sciences which sees the positive side of human behaviour, or at least, is sees human behaviour as an interesting puzzle to be understood rather than altered.

When I went in class to lead my first seminar on popular perceptions of archaeology several years later, I had prepared a powerpoint presentation which introduced my topic with a picture of Indiana Jones. As part of a sociological experiment, I asked the students to identify the person in the picture. All of them were confident that this was Indiana Jones and there was not a single student in the class who did not know him. At the end, I had to disappoint everybody and land them back in reality by saying: “Ladies and Gentlemen, this is not Indiana Jones; this is Harrison Ford, a famous American actor”. It was probably the best way to show them that there is a distinct line between fiction and reality, and also pass the message that a fictional character is not the same as the actual actor playing the role.

Despite that real archaeologists hate any comparison between themselves and Indy, it is a well-hidden fact that most archaeologists have been at some point inspired by this film character. Some archaeologists say it was the whip, the hat and the revolver which impressed them in the first place; however, Clint Eastwood wore the same gear in most of his films without producing any impact on the discipline. Others who indulge into the blurry skies of feminist archaeology see Indiana Jones as a negative influence to the discipline, representing traditional male brutality and phallocratic behaviour. In my opinion, things are a lot simpler than that: it was not the archaeological methodology of Indy that once touched our souls (in fact he never had one), but his sense of adventure, his deep admiration and knowledge of ancient cultures, his interests in foreign languages and exotic places, and his ability in finding solutions under pressure and difficult conditions. Out of all these, it is only the last bit that connects Indiana Jones and the archaeologists of the commercial sector today. In the past, however, archaeologists such as John Pendlebury and Thomas Edward Lawrence probably had more things in common with Indy than with any of us today.

Having replaced the reputation of our most beloved fictional character in the archaeological Pantheon, it is time to move away from fiction to reality, and see what real archaeologists are doing nowadays. Before doing so, I need to stress that there is no such thing as one type of archaeologist. In fact, archaeology is a broader family, consisting of various archaeological species and sub-species.

According to my understanding of things, there are five main species of archaeologists today: students, academics, industrial archaeologists, volunteers and uninvolved bystanders. Please note that I do not recognise amateur archaeologists as proper archaeological species. As there is no such thing as an amateur cardiovascular surgeon, an amateur civil engineer or an amateur airline pilot, in the same way there cannot be an amateur archaeologist. Archaeology is characterised by strict professionalism, following specific methodologies, intensive training and specialisation; therefore, archaeology is as science which demands commitment and cannot be practised as a hobby. Unfortunately, people with natural curiosity in history and archaeology cannot classify as amateur archaeologists. Imagine! Had they an interest in astrophysics, would they classify as amateur rocket scientists? Probably not. Having clarified this detail, it is time to move on and see what each archaeological species stands for.

The student species is not necessarily different to any of the other four. Here, I treat it as a separate entity because it consists of young colleagues at their earliest stage of education and training. Students enter the real world of archaeology after their graduation, so until this happens, they form an intermediate state of archaeological awareness. The student species includes all undergraduates and those who have moved on to Master's degree straight after their Bachelor's. Professional archaeologists returning to university for postgraduate studies and students in full-time research, usually fall under other categories.

The academic archaeological species is characterised by the highest-level of training and specialisation in the discipline, and by an intentional preference in the theoretical and educational side of archaeology. It is notoriously know for its high salaries, which do not reflect the reality of the private sector. Although academic archaeologists have received sufficient training to conduct practical archaeology (e.g. geophysics, digging and handling of archaeological artefacts), in most cases they prefer archaeological research, which is desk based and includes many hours of work at the library or in front of a computer. The academic species can often be actively involved in practical archaeology and excavations; however, this only takes place seasonally and for training purposes. In fact, the focus of academia is to train and prepare future archaeologists for going into the industry, or to conduct independent research in order to enhance the theoretical framework of archaeological interpretation for future generations.

In its negative sense, the academic species is characterised by three disadvantages, which paint the picture of academic archaeology as unrealistic and inefficient. Firstly, it is impossible for them to understand the relationship between cost and efficiency. Despite the presence of deadlines in their work, many of which totally artificial and subject to limitless extensions, their projects rarely suffer from insufficient funding and lack of resources; therefore, they have the annoying privilege of never stressing to finish a project, and never needing to work a normal low-paid job to earn a living. The second disadvantage of the academic species is selectivity: instead of undertaking an entire project from start to completion, they usually prefer isolating specific material or information from another person’s project, and spending a disproportionate amount of time working on it to publication. This attitude leads to the production of biased results and the promotion of selective knowledge, which only satisfies their personal goals. The third disadvantage of academics in over-specialisation. Although it is more than beneficial to have specialised colleagues in our discipline, over-specialisation can be problematic: it often leads to the isolation of academics in archaeology, who can neither interact with the rest, nor contribute towards understanding the broader picture due to the extreme fragmentation of their work.

The industrial archaeological species is notoriously know from its heavy-duty qualities. It is the most actively involved species in archaeology, carrying out exhausting manual labour under extreme weather conditions, and making difficult decisions with limited information under time pressure. Despite the manual nature of their work, industrial archaeologists are still scientists; all of them have academic degrees and have received proper training in dealing with archaeological information. Furthermore, many have received additional training and specialisation at Master's of PhD level, and have nothing to feel jealous about when interacting with their academic colleagues.

In its negative sense, the industrial species is characterised by three disadvantages, which paint the picture of commercial archaeology as highly destructive. Firstly, they are accused of practising archaeology in a careless and non-scientific manner; in reality, however, industrial archaeologists are invited to perform rescue excavations under extreme time pressure with limited resources; therefore, the relationship between cost and efficiency is always dictating the outcome of their work. Secondly, industrial archaeologists are believed to be insufficiently trained and unable to see the broader picture in archaeology. This could be partly true; however, the industrial sector employs many people with high qualifications and advanced understanding of archaeological practice. Such archaeologists could have been producing high-quality publications next to their academic colleagues, had their resources and time been equally unlimited. Thirdly, the academic species mocks the industrial species for their lack of theoretical understanding, which is absolutely true. Unfortunately, the academic species fails to understand the practicalities of industrial archaeology, which are dictated by modern capitalism, and particularly the ‘cost and efficiency’ part.

In an ideal world, archaeological theory and archaeological practice would have been walking hand by hand; in real life, however, practical archaeology has limitations and cannot interact with archaeological theory for two reasons: firstly, because archaeological theory is being developed in an impractical manner for internal consumption within academia; and secondly, because theory is becoming over-abstract and over-imaginative to an extent that it is unlikely to be understood by anybody other than few over-specialised academics. These two reasons characterise the ‘Great Divide’ between academia and commercial archaeology.

The volunteer species is the most attacked yet the most humble of all archaeological species. It is characterised by huge patience, persistence and thirst for knowledge, always satisfied through private financial resources and precious free time. It is sad that other archaeological species consider volunteers to be amateur archaeologists, overseeing that many of them have university degrees. In reality, volunteers are trainees in practical archaeology just as every university graduate, and they are always mentored and monitored by professional archaeologists during their projects. Many volunteers without degrees are highly experienced and well trained at a practical level, matching their qualifications with those of archaeologists with academic training. In many countries, volunteers work on archaeological digs as untrained low-wage workers, and regardless their typical qualifications, they maintain the same level or professionalism as their graduate colleagues.

Unfortunately, volunteers are condemned to work at low-level positions, particularly if they are lacking experience and/or academic qualifications, which is in my opinion wrong. Volunteers are often exploited as cheap labour in archaeology, and are often being mistreated by professional archaeologists, who see them as threat to their own employment. Again, such behaviours are totally unfair to them. The only disadvantage of the volunteer species is its fluctuating interest in archaeology and fluctuating commitment to their projects. Unfortunately, volunteers are often interested in selective pieces of archaeological work, neglecting the totality of archaeology. Furthermore, they are often bored and unmotivated in committing to a project, leading to its abandonment at its most crucial phase. Such behaviour in excavations puts archaeological artefacts and archaeological information at great risk. It is not uncommon among professional archaeologists to believe that any site not excavated at all is in less danger than if excavated by volunteers.

The last species discussed in this section is uninvolved bystanders. The reasons for which uninvolved bystanders comprise an archaeological species of their own will be explained in the next paragraph. Here, it is important to note that not all archaeology graduates end up working in archaeology, and there is absolutely nothing wrong with that. Some graduates realise that the way archaeology is chartered, it is a lot more sensible for them to work in retail, banking or general administration instead of going into the industry. Many times, this is the only way to pay off their student loans, which primarily consist of high tuition fees. Furthermore, by following a different career path, graduates are paid almost the same amount of money as working in industrial archaeology, but without having to deal with manual labour and difficult weather conditions. Such archaeologists have made a conscious decision to work in a different sector for their own personal reasons and their non-involvement in archaeology has nothing sinful.

By contrast, uninvolved bystanders are archaeologists with specific preferences in the discipline, willing to wait until these are satisfied. Such bystanders are usually characterised by high-level training and specialisation at Master's or PhD level, and by a strong preference in high-status jobs. Bystanders are a temporary species resembling students: it is only a matter of time till both get a job and upgrade to another species, but until this happens, bystanders can happily remain unemployed for as long as it takes. Although most of them are passively seeking for an opportunity to arise, some others manipulate people and situations to satisfy their goals quicker. They are arrogant enough to present their research as the most central part of the universe, and are usually constructing their intellectual profile by over-theorising on blurry ideas. Some time ago, I heard somebody referring to this species as ‘strollers’ and this is probably the best way of describing them: they waste limitless time participating in archaeological conferences, trying to promote their ideas and expand their professional circle, hoping that this will one day lead them to their ultimate recognition. Had they been utilising their knowledge in a humbler manner, such archaeologists would have had a lot more things to offer to the discipline; unfortunately, their urge for quick and effortless success is only poisoning the essence of real archaeology. In my exaggerative opinion, such colleagues are a creative bi-product of the current academic system, which sometimes promotes those who can demonstrate excellency without any moral constraints.

The process of ‘becoming’ an archaeologist

Nowadays, it is widely believed that academic studies play major part in the process of becoming an archaeologist, supplemented by field training, which is provided by universities or independent field schools. Graduates who have studied archaeology at university are considered properly educated to be further trained at a practical level as volunteers or trainees, and after doing so, to be fully employed in the archaeological discipline. An interesting question, however, is whether such academic training is sufficient for new graduates. Furthermore, how can some institutionalised training at university reflect the actual conditions encountered in industrial archaeology? Unfortunately, the ‘Great Divide’ between academia and the commercial sector dictates the necessity of having two separate types of archaeological training, at least in Britain.

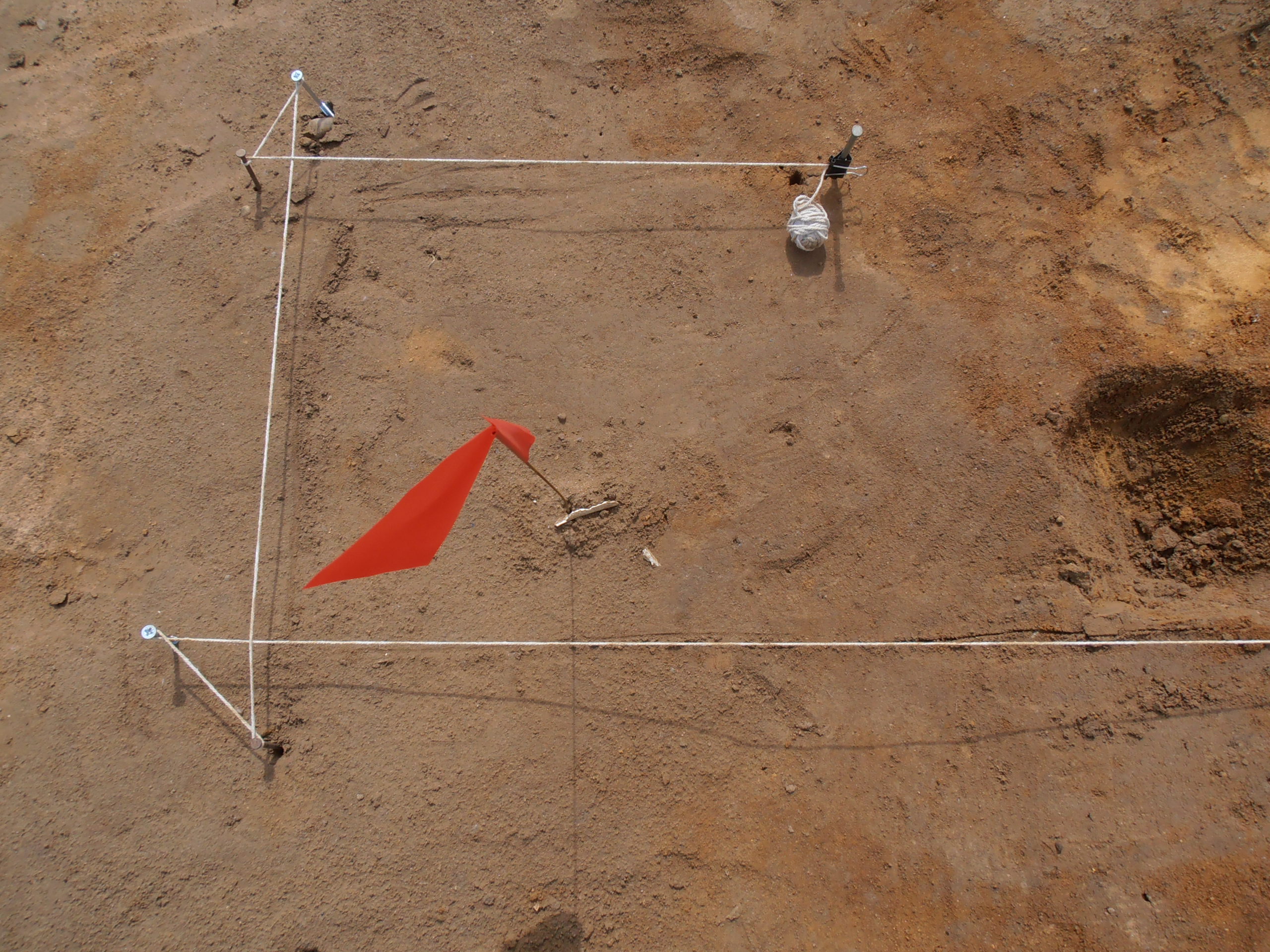

Undergraduate students encounter the practicalities of archaeology for the first time at university-managed excavations, which are conducted seasonally. During such excavations, there is plenty of time for them to test the archaeological methods and techniques they were taught in class, and acquire useful skill, which they will later use in the industry. The first advantage of such projects is that they do not put huge pressure on the students; therefore, there is always time to correct any mistakes and repeat parts of the training that were not understood. Another great advantage is the variety of methods and techniques taught in such projects, even though conservation and post-excavation analysis is rarely included. For such specialisations there are separate field schools, which can be significantly pricey, especially when conducted abroad.

University-managed excavations also have two major disadvantages. Firstly, the conditions under which they take place do not represent reality: the size of such excavations in always manageable; the time-scales and deadlines of such projects are artificial and do not match the pressure encountered in commercial archaeology; their resources can often be unlimited, especially at excavations with collaborating universities abroad; and finally, difficult weather conditions are absent as such digs are normally conducted during the summer. The second disadvantage is that such projects are not always rewarding for the students, at least not in the economic sense. Students are asked to carry out hard manual labour, for which they might never be paid. In many occasions, it is the students who need to pay money for attending a training excavation, and if this is happening away from home, they also need to cover for their accommodation and food.

A slightly different form of training is provided under actual filed conditions in commercial archaeology, at least during the first three or six months of a graduate's employment. Trainees in commercial archaeology are usually university graduates who have finished their academic studies and related training, and have decided to apply for a job in the commercial sector. Their new training is exclusively practical and includes all methods and techniques used in the field, particularly those that are affordable and most commonly encountered among commercial archaeological units. The main advantage of such training is that it covers every bit an archaeologist needs to know without pre-supposing that the trainee has already been taught everything at university. In fact, many archaeologists graduate with little if no field experience at all, while others have over-focused on theoretical or artistic aspects of archaeology. Unfortunately, commercial training does not always include a variety of practical tasks. For example, post-excavation processing is limited and taking place at a secondary level when other pieces of work have already been completed. Furthermore, such training rarely motivates the trainees to develop an interest in specific artefact categories, which might lead them to a specialisation in finds. As opposed to their graduate/volunteer colleagues, trainees in commercial archaeology are being paid a proper salary, although money could be slightly less compared to the salary of a fully trained site assistant.

Having discussed the types of training encountered in archaeology, it is time to discuss what happens if somebody wishes to stay in academia and not go into the industry straight after graduation. This decision is quite common among undergraduate students who wish to specialise further, especially at Master's and PhD levels. In my opinion, this upgrading process is the continuation of a person's archaeological training and broader education, although this is theoretical rather than practical. Given the competition in archaeology nowadays, it is usually a good idea to obtain some additional qualifications and specialisation, particularly if someone does not have enough practical experience in a specific field. Such specialised training could associate with a number of archaeological fields, such as paleoanthropology, osteoarchaeology, forensics, bioarchaeology, geophysics, finds analyses (ceramics, lithics, archaeometallurgy, numismatics, etc.), archaeometry, archaeological computing, graphics and 3D modelling, maritime archaeology, archaeological conservation and epigraphy.

Despite its scientific nature, in its traditional academic sense archaeology still comes down as part of the Arts and the Humanities. In my opinion, this needs to change. Postgraduate students in orthopaedics or zoology are normally awarded with Masters' in Science; however, osteoarchaeologists are normally awarded with Masters' in the Arts, although they are all studying similar subjects. Archaeological specialisation needs to be taken more seriously, starting by changing its status within academia. The technical and practical skills required in the discipline, as well as the increasing importance of modern technologies in our job, all dictate that archaeology needs to be recognised as a highly scientific profession. Such recognition is also likely to bring down the old boundaries that have been established in previous centuries, which restrain archaeology within the sphere of philosophy and art history.

Despite my positive attitude towards archaeological specialisation at academic level, staying in academia could also be unproductive. For example, many colleagues prefer staying in academia for as long as possible, and by doing so, they only postpone going into the industry and working in the commercial sector. It is highly likely that such people will start an archaeological career when it will be too late, and they might not be able to absorb any new information as they will have already consumed most of their time and energy in theoretical approaches. Many archaeologists are also under the impression that following a specialisation will one day lead them to an academic career. This may be true up to a certain extent; but think! How many academic positions are being advertised each year in archaeology? Compared to those advertised in the commercial sector, they are extremely limited.

My positive attitude towards specialisation and my relevant views are the result of personal involvement in British education and commercial archaeology. There are, however, other colleagues who support different views, rejecting the idea of specialisation based on the existing systems in their own countries. For example, the Greek Association of Temporary Archaeologists (Σύλλογος Εκτάκτων Αρχαιολόγων) are openly against specialisation and present their views in an article hosted at their website under the title “Specialisation equals life-long insecurity” (1). In a text resembling a communist manifesto with references to obsolete pseudo-leftish ideas, the Greek temporary archaeologists believe that their colleagues with higher academic qualifications (Master's and PhD degrees) are stealing the jobs from those who are only equipped with a Bachelor's degree. Of course, this argument is not necessarily wrong, and a similar situation is noted in other countries across the Mediterranean, such as Italy. The problem, however, is not specialisation but the structure of the system giving jobs to archaeologists, which is offering extra credits to those with higher academic qualifications. This system is definitely unfair to a large number of graduates. Translating their own words, the Greek Association of Temporary Archaeologists suggests:

“More specifically, the rating of postgraduate qualifications as a prerequisite for the recruitment of archaeological staff automatically invalidates the value of our undergraduate degree, which is the title of vesting our professional rights and our scientific status. For a sector affected by unemployment, job insecurity and flexible working relationships, it is not acceptable to put more and more barriers to our right to work”.

“At the same time, we are opposed to recognising and promoting workplaces of neo-liberal policies for the industrialisation of studies, whose main focus is the 'production' of postgraduate degrees in the context of a peculiar, quantitative, non-qualitative competition, with a lot of 'development' between universities. We do not correlate, in other words, knowledge with specialisation and, more so, the response to the needs and problems that arise in the field of research with the specific logic of specialisation promoted by the EU, governments and universities”.

“The devaluation of our undergraduate diplomas has been systematised over the last decades by the universities themselves, because they adopt the demands of the free market for the transformation of higher education and research -even in the humanities/social studies- to a business-related 'action-field' or 'development field' (Bologna Pact, repeal of Article 16). For this reason, our degree and studies are considered disposable, while postgraduate studies are being promoted and systematised both within universities and in the industry, which has been characterised as a 'labour market' over the past decades. And we are not only against the industrialisation of knowledge and research just because more and more conditions are being added between archaeologists and their right to work, but also because the socio-public role of universities is distorted. We are against this, also because this framework favours those who have the economic resources to refrain from work and carry on retraining (at university), which exacerbates further class distinctions. We are also opposed to the rationale of the 'labour market', which subjects the right-to-work to individual negotiations through the accumulation of specialist qualifications and the production of powerful CVs, and also transforms the archaeological profession from a public/social function to a freelance job” (2).

The Association's views are highly political; they oppose specialisation in academic institutions because this consists of an industrialised act, which also generates a lot of unnecessary competition within archaeology. The discipline is not supposed to satisfy jobs but 'public/social functions'; therefore, the archaeological profession cannot be part of the job market (or 'labour market' as referred in Greek). Although I am planning to return to the above views in the next section of this article, for the time being I would like to stress that the Greek higher education system is unfortunately not connected to the Greek job market. This is not due to a conscious decision of the universities, which are popularly perceived as the promoters of 'education and free thought', but due to the absence of a true market economy. The 'labour market', which the Greek Association of Temporary Archaeologists rejects, is in reality absent! Many professional bodies and unions in Greece, including those in archaeology, are chartered in ways that do not allow outsiders to enter; they are backed by strict government laws, which impose highly restrictive criteria and maintain a level of professional exclusion within all scientific disciplines. In this sense, the only competition that the members of the Association are likely to face, is only internal.

Professional exclusion in Greece begins with the non-recognition of foreign degrees by the Greek state. Although Greece has signed the Bologna Pact, which recognises equal validity of graduate and postgraduate degrees obtained within the EU by all EU countries, the Greek government has established a bureaucratic mechanism, which is supposed to approve the validity of what has already been voted to be valid! Within its own surreal understanding of 'validity', the organisation that approves foreign degrees (DOATAP) demands the submission of a series of documents, which only discourage foreign graduates, and also forces them to pay a large sum of money before they are even allowed to work in Greece. The documents required by DOATAP are listed below in the same order they appear on its website in English (3). In order to underline the linguistic qualifications of the people validating foreign degrees in Greece, I have decided to copy and paste the original list without correcting any of their own spelling and grammar errors:

“Documents required for Recognition of Degrees from foreign Institutions

- Application form (can be provided by the DOATAP secretariat or downloaded from our website).

- Fee of EUR 230.40 (EUR 225 + 2.4% additional charges) for undergraduate titles or EUR 184.32 (EUR 180 + 2.4% additional charges) for postgraduate titles payable to the Bank of Greece (SWIFT CODE: BNGRGRAA, IBAN: GR05 0100 0240 0000 0002 6072 595). In the case of co-examination of titles, both of the above fees are required. On the deposit slip should be referred as depositor the citizen requesting recognition.

- Copy of passport or identity card certified by Greek Official Embassies/Consulates/Greek Lawyers .

- An official statement of law (N. 1599/86) stating:

a. all submitted documents are original.

b. there has been no other application for accreditation to DOATAP or any other Public Authority.

c. the place of study (for all the years of study) - A certified copy of High School Diploma. For non E.U. countries, the U.S.A., the former U.S.S.R. and Canada, one must also submit a certificate issued by a qualified authority of the country (i.e. cultural Attache of the relative Embassy in Greece) stating that the holder of the specific High School diploma has the right to enter higher education.

- A certified copy of the degree to be recognised. The degree must also be verified for authenticity reasons according to the Hague Convention (APOSTILLE). For countries not participating in the Hague Convention, both the degrees and the official transcript should be certified by the Consular Authorities of Greece at the country in which the degree has been obtained. Alternatively, if the degree is not verified as described above, then the official transcript must be sent directly from the University to DOATAP.

- An official transcript (grades from all subjects and from all the years of study, signed and stamped by the University, stating the date of award). If the transcript is not stamped according to the Hague Convention or verified by the Consular Authorities of Greece (for countries not participating in Hague Convention), it must come directly from the University to DOATAP.

- A certificate for the location of studies must be sent by the Institution directly to DOATAP. If the certificate is not written in Greek, English or French, then, additionally, it should, be submitted stamped according to the Hague Convention. The certificate should verify that all applicant’s studies, from …….. to …….., took place and were completed in …………… (country, city, campus) and nowhere else. For PhD degrees with no coursework required, instead of the abovementioned certificate, the Institution should send directly to DOATAP a confirmation letter referring to student’s personal data, study program’s duration and type, graduation date, research supervision and thesis defense. For distance learning studies, instead of the abovementioned certificate, the relevant questionnaire will be completed by the Institution and sent directly to DOATAP.

- A Syllabus / Bulletin of the Institution if either the Institution or the faculty has not been accredited by DOATAP.

- Dissertation / thesis (for postgraduate degrees) along with a greek summary in the case of a doctorate thesis (returned at the end of the recognition procedure)”.

At this point, I need to confess that although I have obtained two degrees at British universities, I still have not gone through the process of validating them in my own country. This is a conscious decision that I made for two reasons. Firstly, because I consider the whole bureaucracy ridiculous and serving an irrational system or professional exclusion. This system is promoted in order to restrict archaeology to what my post-processual and pseudo-left-wing colleagues define as the 'Intellectual Bourgeoisie'. I am sure that once upon a time there used to be mirrors made in the Soviet Union; I am under the impression, however, that my Greek post-processual colleagues never managed to buy one. Secondly, I refuse to validate my British postgraduate degrees because my Greek undergraduate degree, which has been granted to me by an officially established Greek state-university, is not recognised by the Greek state as a valid title! At the moment of writing, it is impossible for me to practise archaeology and ANY other profession as a graduate in my own country, unless I accept a job as a minimum-wage untrained worker or volunteer. On this ridiculous and surreal paradox, I am planning to come back with more information in the following section of my article on employment.

The final question that I wish to discuss in relation to the process of becoming an archaeologist is whether somebody can become one without any academic training. In other words, do we need universities and other institutions to teach archaeology, or could archaeology be taught under field conditions as a practical instead of institutionalised module? This question is difficult for me to answer. As noted in the first section of this article, in my own experience, I definitely benefited from studying archaeology at university. On the other hand though, having started my career as a worker and volunteer in archaeological digs, I am inclined to say that academic training is not always relevant. In Mediterranean countries such as Greece, the archaeological profession is restricted to people with high academic qualifications, while people performing manual tasks in archaeology are minimum-wage untrained workers. In such systems, the recognition of a volunteer or worker as a trained archaeologist is virtually impossible. By contrast, my experience in British commercial archaeology has shown me that people without any previous academic training can often engage in archaeology and sometimes gain enough practical experience to be employed in it. In my opinion, this is a great opportunity for people with natural interest in archaeology to pursue a career without following costly academic studies.

Academic colleagues might challenge my views by suggesting that the contribution of non-graduates in archaeology is limited and so are their career perspectives. Although I can see their point, I must stress that my practical experience in archaeology has also shown me the opposite. Some time ago, when working in Egypt, I had the chance to attend an Austrian archaeological excavation at Avaris, the capital of the Hyksos. It was the first time in my life that I came across the Qufti, a cast of local workers specialised in archaeological excavations, the practical training of whom passes on from father to son since the time of Flinders Petrie (4). Although Qufti workers have no academic qualifications in archaeology, their practical knowledge and experience makes them valuable resources in archaeological digs across Egypt. As an example, during the time when it was difficult for me to recognise different shades of brown, Qufti workers were able to spot the colour of mudbricks dug within thick layers of similarly-coloured mud. This was probably the second time in my archaeological career that I felt like a complete idiot.

The state of ‘being’ an archaeologist

As explained at the beginning of this article, the state of being an archaeologist is associated with employment in the discipline, at least in relation to the points that will be discussed below. The article does not discriminate between full-time and part-time employment, which is also quite common among colleagues working seasonally. Furthermore, the article does not discriminate between employment in the academic and industrial sector, which is a conscious effort towards bridging the 'Great Divide'. Practically, however, one cannot oversee the fact that British commercial archaeology is currently expanding due to important development and infrastructure projects. By contrast, British academic archaeology is prone to severe cuts, most of which associated with a broader decline of interest in the Humanities, high tuition fees, Brexit and the withdrawal of EU funding. This section will primarily focus on employment in British commercial archaeology, and will also discuss the situation in Greece.

What is currently problematic in British commercial archaeology is the lack of sufficient graduates moving into the industry. In many occasions, large projects satisfy their needs by recruiting professionals from other countries, and still, vacancies may never be covered. When I first tried to explain the problem, I believed that high tuition fees at British universities were preventing students from studying courses that were unlikely to offer them 'good jobs'. Such jobs would allow them to pay off their loans as quickly as possible and then move on to making a profit. I also felt that graduates from countries with little or no tuition fees were more likely to accept jobs in British commercial archaeology, and start their careers without the need of paying huge debts. Unfortunately, I soon realised that my approach was too simplistic and the problem was more complicated than I imagined.

When British universities introduced the tripling of their 'home' fees a few years ago, I used to work as a postgraduate assistant-tutor at Cardiff University. What was interesting that year, was that despite the tripling of fees, the numbers of new undergraduate students in archaeology increased. That same year, other universities faced significant drops in the numbers of their archaeology first-year students, which often triggered discussions on shutting down specific departments. Although I could not consider all parameters affecting students' decisions to study archaeology, I felt that I wanted to believe in a positive scenario. My explanation for this paradoxic phenomenon was that more and more teenagers were realising they could not study something they did not like just for the sake of exploiting it financially in the future. I felt that modern teenagers were full of romanticism and ideals, and promoted their personal satisfaction and natural curiosity towards archaeology, instead of imagining big money at another industry after their graduation. In my satisfaction, over the next couple of years I met quite a lot of students that were thinking like this. However, I also met few other students that had a completely different approach towards their studies: their intention was to live the university experience, enjoy student life and partying, then obtain an 'easy degree' and move on to an irrelevant job in banking, human resources, education or the military.

The other thing I realised when I joined British commercial archaeology was that despite the large numbers of foreign archaeologists in the sector (including myself), the majority of graduates were British. I also realised that these young colleagues had proudly paid for each a year of their undergraduate studies a bit more than the total amount I paid for my BA, MA and PhD together. These colleagues never felt they wanted to do anything else in their lives besides archaeology and I am still proud knowing them and working with them. Again, their presence in the industry does not change the fact that demand for new archaeologists is still higher than supply. This is probably due to a significant increase in development projects over the last few years, in a time when the number of archaeologists is relatively steady if not slightly declining.

Of course, there are different cases suggesting that employment of archaeologists is not the same across Europe. For example, Greece is a country with no commercial archaeology and many unemployed archaeologists competing for limited positions. In my opinion, Greece's problem is not the education system and its attitude towards specialisation as noted by the Greek Association of Temporary Archaeologists above, but the criteria for hiring archaeologists and the nature of its economy, which both need to change.

First of all, the existence of temporary (seasonally-hired) and permanent (government-based) archaeologists in the Greek system is by definition disgraceful to our profession, and is only promoting exclusion and segregation within the discipline. Often, when temporary archaeologists in Greece manage to get a permanent job in the public sector, they automatically forget the difficulties of their ex-colleagues in temporary employment, and also criticise their work.

Secondly, it is completely unacceptable for a country full of antiquities such as Greece, to have unemployed archaeologists. The reason this is happening is because the archaeological profession is restricted to supervising tasks, while the actual digging is conducted by either student volunteers or minimum-wage untrained workers. Furthermore, such supervising jobs are only advertised seasonally and recruitment is conducted on a point system basis, which excludes most of the applicants and favouritises specific candidates over others.

Thirdly, such problems would have been easily resolved, not by modifying the existing application and employment system in archaeology, which is state-managed, but by generating a legal framework that would allow private archaeological units to operate under government supervision. In simple words, the only answer to unemployment in Greece is the creation of new jobs through the promotion of a market economy, which will lead to the creation of a 'labour market'.

This concept is completely demonised and anathemised by the majority of Greek archaeologists. Such colleagues insist on wearing their pseudo-ideological blinkers, associating our profession with restricted government-controlled functions once encountered in obsolete communist regimes. In my opinion, this attitude derives from seeing modern capitalism as the ultimate of all threats. Such views are again noted in another article of the Greek Association of Temporary Archaeologists, where they comment on the Memorandum of Understanding and Cooperation, which was recently co-signed by the Greek Ministry of Culture and Tourism and the Ministry of Infrastructure, Transport and Networks (5) :

“The Association of Temporary Archaeologists argues that under no circumstances should 'understanding' and 'cooperation' be organised at the expense of archaeology and culture. It is unacceptable to hide the devaluation of the historical monuments and the devaluation of the work of the employees in the heritage sector behind the negotiations and agreements of various ministries. We must protect, preserve and highlight the cultural products that the country has to offer, which are the property of the Greek people (6), and under no circumstances we will allow these to be sacrificed for the growth and quick profit of contractors and companies” (7).

It is relatively clear that even the Greek archaeologists who are arguing against the existing system in Greece do not really want any development to take place; instead, they are interested in a stricter legislation limiting development and private initiatives, and the continuation of the existing Status Quo of a small state-centric and nearly bankrupt economy. They also feel that this attitude will paradoxically generate more jobs for the archaeologists, meaning new supervisory roles similar to those advertised today, instead of actual digging and post-excavation jobs. In my opinion, the whole argument is self-contradicting if not surreal and coming from the minds of people who do not have the faintest idea of how modern economies work. Whenever I ask my Greek colleagues who will pay for such projects, I always receive the same answer: “the state will cover the cost because it is the state's responsibility to promote national cultural heritage”. I am not entirely sure if this has actually worked during the past, though I totally agree that in an ideal world this would have been the case; however, under the present economic situation in Greece and despite the extreme -if not lethal- over-taxation of the society, there does not seem to be enough money to be spent on large scale government-planned excavations, and there is definitely no development in the private sector to guarantee that money might flow in the future.

Another problem in Greece is that the archaeological profession is not open to everybody. Even though many people have studied to become archaeologists, those who are actually allowed to work in archaeology are only a small fraction. As there are no commercial archaeological units in Greece, all vacancies are advertised by local government bodies called Ephorates. The Ephorates are also responsible for approving any form of development that is likely to be associated with the historic environment. Whenever there is need for a developer or contractor to hire an archaeologist, this cannot happen as part of a private agreement; the archaeologist can only be hired by the developer or the contractor if he/she has been first approved for this specific task (and this task only) by the local Ephorate. To do so, the local county Ephors, who are permanent civil servants in the archaeological services, advertise a vacancy to be filled by a temporary archaeologist, who will have to compete with others based on a set of strict and highly specific criteria. In order to match those criteria, candidates need to gather a series of documents to prove their academic qualifications and work experience; validate them through the government’s bureaucracy; and submit them in the form of a portfolio to the Ephorate. Whoever scores more points according to his/her qualifications gets the job. Depending on the county where the Ephorate is based and depending on the vacancy, there might be slight variations to the job criteria; however, the basic requirements are generally the same all over the country as these have been established by the same ministry.

To demonstrate the degree of bureaucracy, discrimination and professional exclusion characterising Greek archaeology, I am planning to go through each one of these criteria and comment on their absurdity. Some colleagues of mine might argue that the reason I am doing so is because of my own disappointment from the Greek system: after all those years of training and hard work, I still do not officially qualify to work as an archaeologist in my own country! I wish to clarify to my colleagues, however, that I have absolutely no disappointment issues with the Greek system for three reasons: firstly, because I never took it seriously; secondly, because it always presented itself as 'The Forbidden Fruit' and it never occurred to me that one day I might apply for a job there; and thirdly, because my principles do not allow me to be part of it anyway. The job criteria below (8) (translated in English by myself) were downloaded from an advertised vacancy posted at the Greek government’s website (9) at the time of writing. The same criteria were noted in almost every other advertised vacancy in archaeology posted at the same website and will not be repeated here.

The first requirement for getting a job in Greek archaeology is: “a Bachelor's degree from the Greek School of Philosophy and its department of History and Archaeology, or a Bachelor's degree from the Greek School of Philosophy and its department of History and Archaeology with specialisation in Archaeology, or the equivalent of the same foreign specialisation recognised by the DOATAP”. In other words, the only people who are allowed to work in Greek archaeology are the undergraduates of a single School, holding a bachelor's degree in archaeology or a joined degree in history and archaeology together. Graduates from other Greek University Schools associated with neighbouring disciplines (e.g. history, philology, classics, etc.) and Bachelor's holders in partly associated disciplines (e.g. geology, anthropology, forensics, material sciences, etc.) can NEVER get a job in Greek archaeology, even if they have studied archaeology at postgraduate level! As for those that have a Bachelor's degree in archaeology from an non-Greek university, they first need to get their foreign title recognised by the Greek state (through DOATAP) by paying a large sum of money and by submitting a long list of translated documents, which were discussed in the previous section of this article. The tricky part for foreign graduates is that if their title does not translate literally as “Bachelor's in History and Archaeology with specialisation in Archaeology”, the Ephorate will reject their application.

The next criteria for getting a job in Greek archaeology are the “excellent knowledge of English, French, German or Italian”, supplemented by an “appropriate knowledge of computer use in the areas of: a) word processing, b) spreadsheets, and c) internet services”. The only way to prove such qualifications is by submitting relevant certificates issued by official foreign language representatives in Greece and certificates from the local ECDL foundation for informatics. Since 2003, the only official certification for foreign languages in Greece is the Greek State Certificate of Foreign Languages Proficiency. Other certificates, which are issued by language certification schemes controlled by foreign institutions based in Greece, such as the British Council, the French Institute or the Goethe Institute, are only accepted 'transitionally'. For some weird reason, Presidential Decree 347/03, section 19.2, does not define the length of this transitional period, which until today remains unknown (10). It is interesting that the holders of foreign postgraduate degrees in any of the above languages, could not use their titles to prove their excellent knowledge in such languages, at least before 2003; and although Presidential Decree 347/03 was a step forward for the recognition of the dual role of foreign titles as professional and linguistic certifications, there are a couple of points that still remain unclear. Firstly, are these valid for permanent-only positions in the Greek public sector, or do they also apply for temporary positions? And secondly, could a candidate submit a foreign degree as a language certificate without validating it through DOATAP? Personally, after a PhD and three years of teaching experience in a British university, I still cannot prove my excellent knowledge in English to the Greek Ephorates. A similar problem can be noted in relation to proving appropriate knowledge of computer use. For example, a candidate with a second Bachelor's degree in computer science cannot use this as evidence of appropriate computer knowledge, unless such certificate is specified to be an acceptable form of evidence in the job description.

In terms of professional qualifications, the applicants for archaeological jobs need “proved experience (of at least 6 months) related to the subject of the position (as this is defined in the ASEP appendix and refers to 60% of the positions declared)”. ASEP stands for “Highest Council of Staff Selection” for the Greek public sector and is the authority regulating public employment. According to the existing regulations, proved experience in Greek archaeology is any work associated with excavations or other projects conducted by the Ephorates, and nothing else. This means that applicants with strong voluntary archaeological experience, or a record of archaeological excavations abroad, are not accepted as suitable candidates.

Despite their ridiculously restrictive criteria, Ephorates can be relatively flexible just in case Mr. Perfect never shows up. For example, job advertisements explain that “if there are no candidates who can demonstrate excellent foreign language skills, then those who can demonstrate very good or even good knowledge of a foreign language, are likely to be considered”. Of course, this flexibility means absolutely nothing when all candidates are supposed to have graduated from one specific School only, and to have worked under one specific employer only.

Perhaps as the result of a pointless attempt towards positive discrimination, Ephorates recruit 60% of archaeologists with relative experience and 40% with no experience at all. In fact, they even specify that “if 60% of the positions is not covered by experienced candidates, then the remaining posts will be filled by candidates without experience; if 40% of the positions are not covered by unqualified candidates, then the remaining posts will be covered by qualified candidates”. Personally, I fail to understand the maths behind such percentages, simply because every advertisement I found online was only asking for one archaeologist per job!

The above criteria prove that the whole system in Greek archaeology is designed to promote exclusion and unemployment. Furthermore, the system is structured to promote its own favourable 'strong candidates': those matching the exact criteria, which are the same across every advertised vacancy, will eventually monopolise all available jobs. Had the system been fair, it would have promoted task-specific job descriptions instead of asking for the same qualifications for all jobs. Secondly, it would have allowed a larger number of candidates to participate in the procedures.

As professional bodies, Greek archaeological associations are making things even worse by refusing to support development and a market-based framework for archaeological practice. Adding the broader lack of development in Greece due to its insecure economic environment, bureaucracy and corruption, and adding the continuity of economic recession on top, it is highly unlikely that the unemployment of archaeologists is going to be tackled soon.

Epilogue

To summarise my points, although academic studies play important role in the process of becoming an archaeologist, these are not the only ones. People with natural talents and practical experience can also become archaeologists IF the system and local legislation allow this to happen. The cost of studying archaeology nowadays is high and in most cases it cannot match the salary of a new graduate; therefore, archaeological training and employment should also be regulated outside academic institutions.

Another problem is that certain people with academic qualifications may never manage to become practising archaeologists. The existing systems in many countries across the world raise forbidding boundaries, complexities and bureaucratic obstacles in order to prevent new graduates from working in archaeology. The Greek paradox may sound too extreme; however, one must bear in mind that the entire system and economic structure of the Greek society is still based on professional protectionism and exclusion.

The way development takes place nowadays, archaeologists face better employment perspectives in countries operating under market-based economic systems. If archaeology is viewed as a public socio-cultural function instead of a paid job, which is the cases in countries such as Greece, the discipline is condemned to lose a lot of if its qualified personnel in the future. A decline in the numbers of professional archaeologists will only benefit a small fraction of colleagues, the rights of whom have already been protected under legislations promoting exclusion. Even in market-based economies, if employment becomes an issue, then the majority of archaeology graduates will easily turn to completely different industries. In that case, non-trained workers and volunteers will be asked to fill in the gap without having any employment rights and recognised qualifications, which will produce more problems to the industry.

Notes:

- The article, which is written in Greek, can be fount at:

http://www.seka.net.gr/s/o-sullogos-mas/theseis/131-%CE%B5%CE%BE%CE%B5%CE%B9%CE%B4%CE%B9%CE%BA%CE%B5%CF%8D%CF%83%CE%B5%CE%B9%CF%82-%CE%AF%CF%83%CE%BF%CE%BD-%CE%B4%CE%B9%CE%B1-%CE%B2%CE%AF%CE%BF%CF%85-%CE%B5%CF%80%CE%B9%CF%83%CF%86%CE%AC%CE%BB%CE%B5%CE%B9%CE%B1 - “Πιο συγκεκριμένα, η ιεράρχηση των μεταπτυχιακών τίτλων ειδίκευσης ως προϋπόθεσης για την πρόσληψη του αρχαιολογικού προσωπικού ακυρώνει αυτομάτως την αξία του πτυχίου μας, που είναι ο τίτλος κατοχύρωσης των επαγγελματικών μας δικαιωμάτων και της επιστημονικής μας ιδιότητας. Για έναν κλάδο που πλήττεται από την ανεργία, την εργασιακή επισφάλεια και τις ελαστικές σχέσεις εργασίας, δεν είναι ανεκτό να τίθενται όλο και περισσότεροι φραγμοί στο δικαίωμά μας για δουλειά”.

“Παράλληλα, είμαστε αντίθετοι στην αναγνώριση και στην προώθηση στους χώρους δουλειάς των νεοφιλελεύθερων πολιτικών εκβιομηχάνισης των σπουδών, που βασικός της άξονας είναι η "παραγωγή" μεταπτυχιακών τίτλων σπουδών στο πλαίσιο ενός ιδιότυπου, ποσοτικού, όχι ποιοτικού, ανταγωνισμού, με μπόλικο άρωμα "ανάπτυξης", μεταξύ των ΑΕΙ. Δεν ταυτίζουμε, δηλαδή, τη γνώση με την ειδίκευση και, πολύ περισσότερο, την ανταπόκριση με τις ανάγκες και τα προβλήματα, που ανακύπτουν στο ανασκαφικό πεδίο με τη συγκεκριμένη λογική ειδίκευσης που προωθείται από την Ε.Ε., τις κυβερνήσεις και τα πανεπιστήμια. Η απαξίωση των πτυχίων μας συστηματοποιείται τις τελευταίες δεκαετίες από τα ίδια τα πανεπιστήμια, γιατί υιοθετούν τις επιταγές της ελεύθερης αγοράς για μετατροπή της ανώτατης παιδείας και της έρευνας, ακόμα και στις ανθρωπιστικές-κοινωνικές σπουδές, σε επιχειρηματικό πεδίο δράσης ή αλλιώς σε πεδίο "ανάπτυξης" (σύμφωνο Μπολόνια, κατάργηση άρθρου 16)”.

“Για το λόγο αυτό το πτυχίο και οι σπουδές μας θεωρούνται αναλώσιμες, ενώ οι μεταπτυχιακές σπουδές προωθούνται και συστηματοποιούνται τόσο εντός των πανεπιστημίων, όσο και στην παραγωγή, η οποία χαρακτηρίζεται τις τελευταίες δεκαετίες ως αγορά εργασίας. Και δεν είμαστε ενάντιοι στην εκβιομηχάνιση της γνώσης και της έρευνας μόνο επειδή προστίθενται όλο και περισσότερες προϋποθέσεις ανάμεσα στους αρχαιολόγους και το δικαίωμα τους για δουλειά, ούτε επειδή διαστρέφεται ο κοινωνικός-δημόσιος ρόλος των πανεπιστημίων. Είμαστε ενάντιοι και επειδή το πλαίσιο αυτό ευνοεί όσους έχουν τα προς το ζην για να απέχουν από την εργασία και να συνεχίσουν να μετεκπαιδεύονται, εντείνοντας ακόμα περισσότερο τις ταξικές αντιθέσεις. Είμαστε ενάντιοι και απέναντι στη λογική της αγοράς εργασίας, που θέτει το δικαίωμα στη δουλειά σε ατομική διαπραγμάτευση, μέσω της συσσώρευσης τίτλων ειδίκευσης και της κατάρτισης ισχυρών βιογραφικών, και μετατρέπει το επάγγελμα του αρχαιολόγου από δημόσιο-κοινωνικό λειτούργημα σε ελεύθερο επάγγελμα”. - The original list can be found at:

http://www.doatap.gr/en/dikaiolog.php - for more information see Doyon, W., 2015, 'On Archaeological Labor in Modern Egypt', in Carruthers, W. (ed.) Histories of Egyptology: Interdisciplinary Measures, New York: Routledge, 141-56.

- The article, which is written in Greek, can be fount at:

http://www.seka.net.gr/s/o-sullogos-mas/theseis/22-mnimonio-synantilipsis-kai-synergasias-metaksy-yppot-ypypomedi - My disagreement to this point, and the reasons why Greek antiquities are not treated as the property of the Greek people, have already been discussed in a previous article under the title “Creationism and the creative commons madness - Part 3: The arts and the humanities”, and under the section “Owning archaeological material in Greece”.

- “Ο Σύλλογος Εκτάκτων Αρχαιολόγων υποστηρίζει ότι σε καμία περίπτωση δεν πρέπει η «συναντίληψη» και η «συνεργασία» να οργανωθούν σε βάρος της αρχαιολογίας και του Πολιτισμού. Είναι απαράδεκτο να κρύβεται η απαξίωση των μνημείων και η υποτίμηση του έργου των εργαζομένων στον χώρο του Πολιτισμού πίσω από τις διαπραγματεύσεις και συμφωνίες των Υπουργείων. Οφείλουμε να προστατεύσουμε, να διατηρήσουμε και να αναδείξουμε τα προϊόντα πολιτισμού που έχει να επιδείξει η χώρα, τα οποία αποτελούν κτήμα του ελληνικού λαού και τα οποία, σε καμία περίπτωση, δεν θα επιτρέψουμε να θυσιαστούν στο βωμό της ανάπτυξης και του γρήγορου κέρδους εργολάβων και εταιρειών".

- I am posting the job criteria in Greek, precisely as these were advertised:

“Πτυχίο Φιλοσοφικής Σχολής τμήματος Ιστορίας και Αρχαιολογίας, ή Πτυχίο Φιλοσοφικής Σχολής τμήματος Ιστορίας και Αρχαιολογίας με ειδίκευση στην Αρχαιολογία, πανεπιστημίου της ημεδαπής ή ισότιμο αντίστοιχης ειδικότητας της αλλοδαπής αναγνωρισμένο από το ∆ΟΑΤΑΠ.

Άριστη γνώση της αγγλικής, ή γαλλικής, ή γερμανικής, ή ιταλικής γλώσσας.

Αποδεδειγμένη γνώση χειρισμού Η/Υ στα αντικείμενα: α) επεξεργασίας κειμένων, β) υπολογιστικών φύλλων, γ) υπηρεσιών διαδικτύου.

Αποδεδειγμένη Εμ̟πειρία (τουλάχιστον 6μηνη) συναφή με το αντικείμενο της ̟προκηρυσσόμενης θέσης (όπως ορίζεται στο παράρτημα του ΑΣΕΠ και αφορά το 60% των, προκηρυσσόμενων θέσεων).

Αν δεν υπάρξουν υποψήφιοι, οι οποίοι να διαθέτουν το προσόν της άριστης γνώσης ξένης γλώσσας, μπορούν να επιλεγούν και υποψήφιοι και με πολύ καλή γνώση ή ακόμη και καλή γνώση ξένης γλώσσας.

Σε περίπτωση ̟που οι θέσεις της ποσόστωσης 60% δεν καλυφθούν από υποψηφίους με εμπειρία τότε οι υπολειπόμενες θέσεις θα καλυφθούν από υποψηφίους χωρίς αυτή”.

Σε περίπτωση που οι θέσεις της ποσόστωσης 40% δεν καλυφθούν από υποψηφίους χωρίς εμπειρία τότε οι υπολειπόμενες θέσεις θα καλυφθούν από υποψηφίους με αυτή. - Such vacancies are advertised at:

www.diavgeia.gov.gr - The Presidential Decree 347/03 can be found at:

http://www.dsanet.gr/Epikairothta/Nomothesia/pd347_03.htm