Report on a small worked stone assemblage from Dorset

Attention: Important Disclaimer

This paper is a recent modification of a mock report on a small lithic assemblage. The original report was a marked assignment for the University of Southampton, during the author’s MA studies between 2008 and 2009. The aim of the original assignment was to prepare the graduate to produce basic archaeological reports on lithic assemblages. The lithic material that is discussed in this paper is real and was handed to the author by a UK commercial archaeology unit, which still reserves the publication rights for the site report and its excavated material.

To avoid any complications, the author decided not to upload his original assignment on the web due to certain copyright issues and out of professional courtesy to the archaeological unit, which originally handled the assemblage. The current paper presents the author’s own analysis and discussion of the material, including personal illustrations and photographs, which are still the author’s own intellectual property. The location of the archaeological site, where the material comes from, and other information related to its excavation have been purposely altered.

The author clearly states that the publication of his work on his personal website does not consist of a commercial activity and does not aim towards economic profit. By contrast, the author wishes his work to be publicly available for free and to be shared openly among those interested in reading it, particularly students in the analysis of ceramics and lithics, who might be looking for examples of finds reports.

Introduction

This finds report discusses six worked stone objects that were recovered from the Late Iron Age – Early Roman settlement of Bethlehem Farm, Dorset. The report is divided in three artefact groups: mortars, quernstones and a possible whetstone. The location of Area 52 and the broader archaeological site of Bethlehem Farm are noted by Davies (1964, 75).

Mortars

Three mortar fragments were recovered from the site’s topsoil. Although unstratified, such fragments suggest domestic activities dating in the Roman period. All fragments are made of local Purbeck Limestone, which is the main geological formation in the local vicinity (Davies, 1964). Hand specimen examination shows that the three fragments come from three different mortars. More specifically:

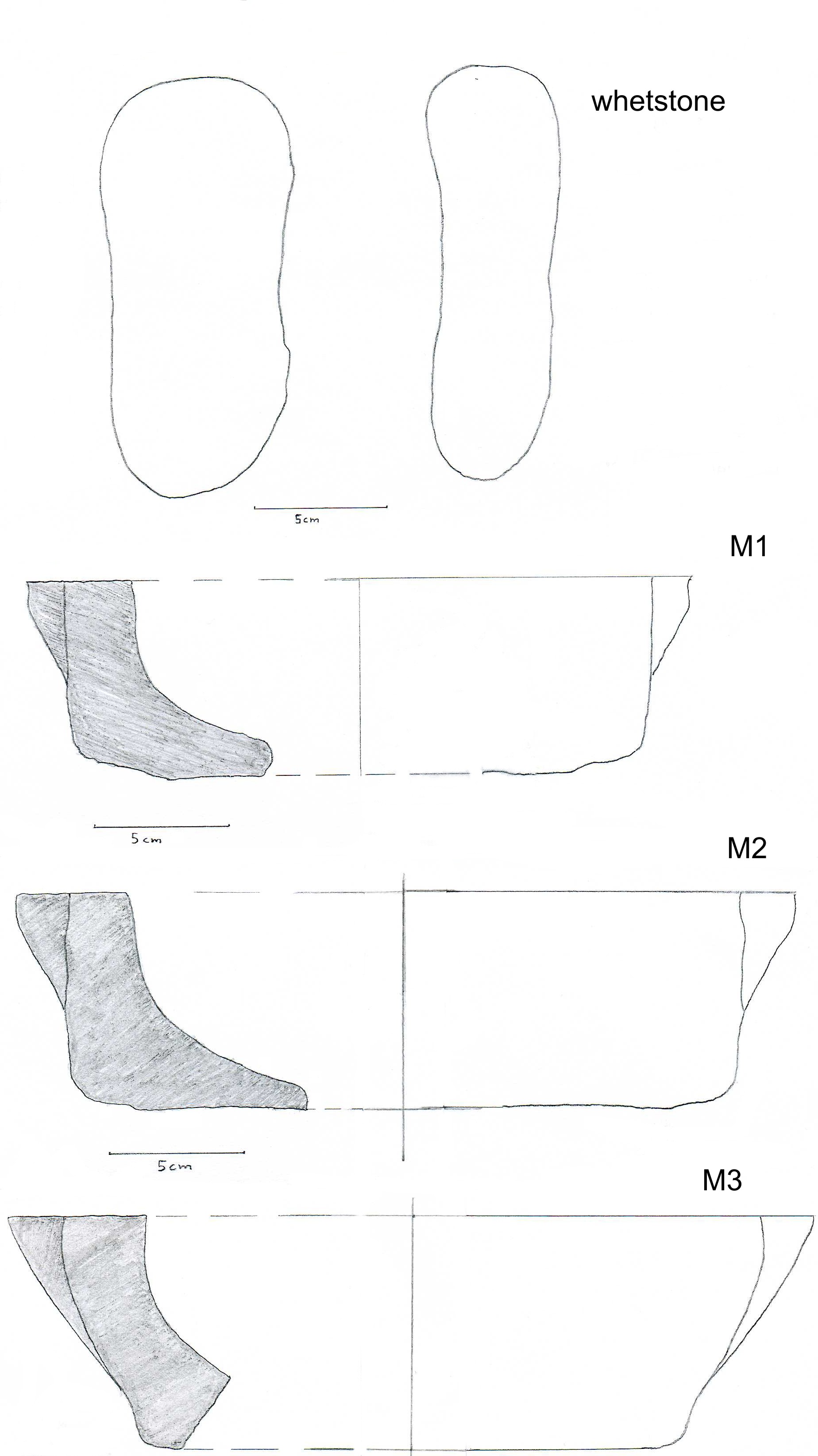

Figure 1: Mortars

M1 (Figure 1, n.1 and Figure 2, M1) is 12cm X 10.2cm and its wall thickness ranges between 2.6cm and 3.5cm. It weighs 627gr and it comes from a mortar with 22cm external diameter.

M2 (Figure 1, n.2 and Figure 2, M2) is 15.4cm X 9.8cm and its wall thickness ranges between 2.1cm and 3.6cm. It weighs 913gr and it comes from a mortar with 25cm external diameter.

M3 (Figure 1, n.3 and Figure 2, M3) is 12.3cm X 10.6cm and its wall thickness ranges between 2.2cm and 3.6cm. It weighs 573gr and it comes from a mortar with 28cm external diameter.

Figure 2: Illustrations of whetstone and mortars

Quernstones

Two quernstone fragments were recovered from the site’s topsoil layer. The quernstones are made of Upper Greensand which consists of fairly large and angular pieces of quartz. According to Davies (1964), Upper Greensand is also common in narrow zone crossing Dorset from South-East to North (Davies, 1964). A fresh break on one of the fragments suggests the presence of Fossiliferous Greenstone, similar to other samples from the quarry of Pen Pits on the Wiltshire - Somerset - Dorset boarder (Crawford 1953, 100). Hand specimen examination suggests that both fragments derive from two quernstones of different size. The bottom surfaces of both fragments are heavily worn, indicating extensive use. Their top surfaces carry deep pecking marks.

Figure 3: Quernstones

Q1 (Figure 2, n.1) is 13.7cm X 11.8cm and its thickness ranges between 3.6cm and 4cm. It weighs 921gr and is estimated to come from a quernstone with 45cm diameter. The top side of this fragment carries a small circular mark from oxidized iron, 1.1cm in diameter. It is probably due to post-depositional contact with a metal object. Nothing suggests that the oxidised spot might have been caused by the oxidisation of a metal rod or mechanical part attached on the original quern.

Q2 (Figure 2, n.2) is 10.3cm X 9.6cm and its thickness ranges between 3.8cm and 4.5cm. It weighs 565gr and it is estimated to come from a quernstone with a diameter between 40cm and 45cm.

Whetstone

One possible whetstone, made of local Purbeck Limestone, was recovered from the site’s topsoil. The shape of the stone suggests that it was probably used as a sharpening and percussion tool (Figure 3; Figure 2). This possible whetstone is 16.1cm X 7.6cm and weighs 915gr. Its examination under a X20 compound microscope did not show any scratches or other linear patterns of use wear, which are likely to suggest sharpening of pointy metal objects (e.g. needles). Two short linear marks are certainly due to deposition. One of the stone’s curved edges carries chipping and hammering marks. The stone’s surface curves smoothly towards its centre. Its thickness fluctuates between 4.7cm towards the edges and to 4.2cm towards the centre. Furthermore, the stone’s colour fades towards the centre, which is likely to suggest that the central part of the stone has been worn due to the sharpening of flat metal objects (e.g. knives). Due to its multiple use-wear marks, this specific stone tool classifies as both hammer and whetstone.

Figure 4: Whetstone

Discussion

The analysis of the worked stone assemblage from Area 52, Bethlehem Farm, Dorset, suggests that the inhabitants of the Late Iron Age and Early Roman settlement accessed and utilised local stone resources. The extraction, processing and use of local stones coincides with a regional pattern. Similar quernstones, made of Upper Greensand, have also been recovered from the Iron Age and Early Roman settlement of Shapwick (Papworth 1997). Same types of mortars, made from Portland Limestone, along with quernstones and millstones made of Upper Greensand, have been recovered from the Roman villa at Halstock (Lucas 1993). Even though there are no similar examples of local sharpening tools, it is generally argued that local (Jurassic Purbeck Limestone), regionally imported (e.g. Cretaceous Kentish Rag) and other ‘exotic’ hone-types were used in the vicinity throughout the Roman period (Moore 1978; Moore 1983).

In relation to their national significance, Roman milling stones were usually extracted from local quarries. For example, the use of local Carboniferous Millstone Grit associates with milling activities in Derbyshire and Norfolk (Moore 1983, 291). Other evidence suggests the exploitation of Millstone Grit from the Pennines, Devonian Quartz Conglomerates from the Forest of Dean, Hertfordshire Puddingstone and finally, Greensand from the Hythe beds of Sussex (Peacock 1980, 43-4). It is generally argued that in Roman Britain small hand-mills, such as the ones recovered from Bethlehem Farm, were usually supplied by local production centres and their distribution ranged between a few tens and several hundreds of kilometres (Peacock 1980, 44).

Although local millstones were popular in the area, the importation of foreign millstones was not unknown during the Roman period. The majority of imported millstones in Britain, particularly between the 1st and 2nd century AD, were believed to originate from Mayen, Niedermendig, or the Eifel Hills of Germany. Such imported millstones are mostly found in East Anglia, the Thames Valley and further North, and are often associated with the presence of the Roman armies (Peacock 1980, 49-50). Based on our current knowledge, the production of Roman millstones in the vicinity of Bethlehem Farm was solely depended on local resources.

Bibliography

Crawford, O.G.S., 1953, Archaeology In The Field, London: Phoenix House .

Davies, G.M., 1964, The Dorset Coast: A geological guide, London: Adam and Charles Black.

Lucas, R.N., 1993, The Romano-British Villa at Halstock, Dorset, Excavations 1967-1985, Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society Monographs Series (13).

Moore, D.T., 1978, ‘The petrography and archaeology of English honestones’, Journal of Archaeological Science (5), 61-73.

Moore, D.T., 1983, ‘Petrological aspects of some sharpening stones, touchstones, and milling stones’, in Kempe, D.R.C. and Harvey, A.P. (eds.) The Petrology of Archaeological Artefacts, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 277-300.

Papworth, M., 1997, ‘The Romano-British settlement of Shapwick, Dorset’, Britannia (28), 354-358.

Peacock, D.P.S., 1980, ‘The Roman millstone trade: a petrological sketch’, World Archaeology 12(1), 43-53.